Stunning Lawsuit Accuses Texas Election Officials of Failing to Protect Ballot Secrecy — And Now the Texas GOP Chair’s Ballot Has Been Leaked

Ralph Barrera/Austin American-Statesman via AP.

The Eyes of Texas are upon you,

All the livelong day.

The Eyes of Texas are upon you,

You cannot get away.

Do not think you can escape them

At night or early in the morn —

The Eyes of Texas are upon you

Til Gabriel blows his horn.– “The Eyes of Texas,” school spirit song of The University of Texas at Austin

The eyes of Texas were upon the ballots cast by several high-profile Texas politicians on Wednesday, after documents were leaked related to a stunning lawsuit accusing state election officials of failing to properly protect ballot secrecy. The leak included the purported ballot for the chairman of the Republican Party of Texas (RPT) — catching him in a lie about how he voted in the presidential primary.

The 77-page complaint was filed by an elections security researcher who lives in Williamson County, Texas and four other Texas voters, two of whom also live in Williamson County, one from Bell County, and one from Llano County. Texas Secretary of State Jane Nelson, Director of the Division of Elections Christina Adkins, and the county election administrators for Williamson, Bell, and Llano Counties are named as defendants, accused of “willful and systematic disregard of election laws” that put at risk the secrecy of potentially millions of ballots cast by Texans in recent elections.

The complaint describes the plaintiffs as all “consistent voters” who “voted in the most recent Texas elections in November 2023 and March 2024,” but either do not qualify to vote by mail under Texas law or prefer to vote in person.

This is an issue, the complaint explains, because the state has an interest in “preventing, detecting, and punishing fraud and ensuring the integrity of Texas elections,” as enshrined in the Texas Constitution and Texas Election Code, but the way some counties treat in-person voters fails to protect ballot secrecy:

Texans who vote by mail receive a consecutively-numbered paper ballot that preserves that secrecy. However, many Texans who vote in person, including Plaintiffs, have no choice but to use paper ballots that lack consecutive numbers. Instead, the paper ballots Plaintiffs have been required to utilize at the polls contain computer-generated randomly assigned unique identifier “ballot tracking” numbers, which do not comply with Texas law and, importantly, do not preserve the secrecy of Plaintiffs’ ballots, as described more fully herein. As a result, Plaintiffs are relegated to a class of in-person voters whose votes are neither assured secrecy nor protected from being undermined, diluted and debased by lawlessness and fraud.

A substantial section of the complaint details the various technology for the electronic poll books, electronic voting machines, and software used in the affected counties, and how “unique identifier ballot numbers” are printed on every in-person ballot cast therein, resulting in an actual ballot being traceable back to the actual name of the voter who cast it.

All Texas counties use electronic voting machines that generate printed ballots to create an “auditable paper trail” and in the counties at issue in this lawsuit, the unique identifier ballot number is generated and assigned to each voter after they physically arrive at the voting location and check in, and then printed on the voter’s actual paper ballot before the ballot is placed into the ballot scanner.

The technology used by the affected counties does allow the use of consecutive numbers that would not be generated anew for each voter and not traceable back to them, but these county election administrators have chosen not to do so, and the state officials are not forcing them to comply with state law, the complaint alleges, despite there being “no technical or logistical limitations on the County Defendants implementing consecutive numbering of ballots” instead of using these “illegal and unconstitutional” uniquely assigned numbers.

Secretary of State Nelson is highlighted for specific culpability for an email she sent in 2019 to county clerks and election administrators saying that consecutively numbered paper ballots were now optional, which the complaint attacks as being “in complete contravention” of the Texas Election Code and “violating Plaintiffs’ due process rights to participate in the law-making process of representative government” with this “disparate, unequal treatment between the classes of in-person and by-mail voters.”

To be clear, the voter’s name is not printed on the ballot, but data files obtainable through standard public records requests were able to be used to cross-reference a voter’s ID, the unique identifier ballot number, and the actual ballot.

A source familiar with the investigation behind the lawsuit told Mediaite that the plaintiffs’ research and legal team used the public election files to look up ballots for the plaintiffs and then multiple prominent Texas politicians, including Gov. Greg Abbott (R), the Williamson County Sheriff, county judges, county commissioners, and Republican Party of Texas (RPT) chair and State Rep. Matt Rinaldi (R), shown above in a verbal altercation with another Texas GOP House colleague. These public officials were chosen to illustrate the ease of accessing the election data files without targeting private citizens, the source explained.

The actual method used to cross-reference the unique identifier ballot numbers with the voter names and the results from individual ballots were originally filed in redacted form with the complaint (a redacted presentation by a Texas A&M University computer scientist regarding the methodology available for download here), according to our source. Rumors have been flying around Texas political circles in recent weeks about the method mentioned in the lawsuit and whether or not Texans’ ballots were really at risk of exposure.

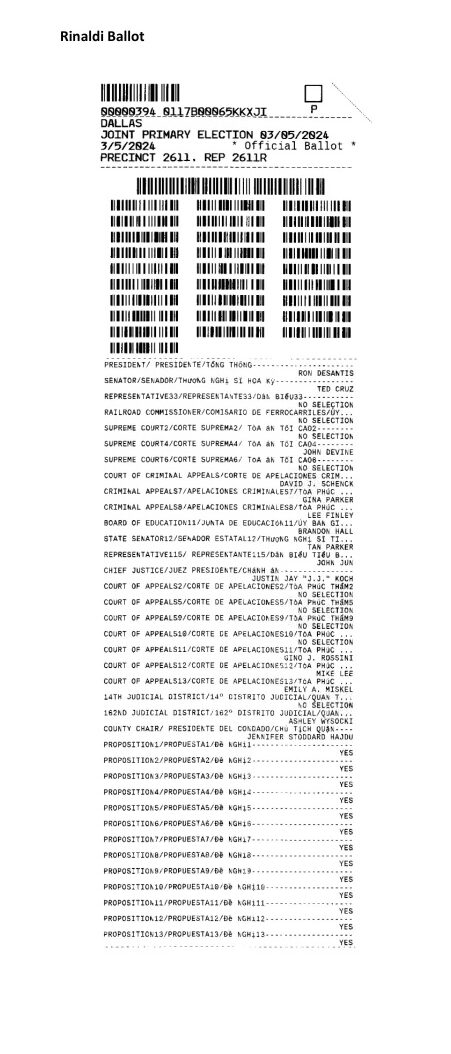

And then on Wednesday, Texas-based website Current Revolt published documents that were produced using the methodology deployed in the investigation for the lawsuit – specifically, Rinaldi’s ballot.

Rinaldi voted in person in Dallas County for the Texas GOP presidential primary in March. He had publicly endorsed former President Donald Trump, said he voted for him, and even continued to insist earlier this week that he had cast his vote for Trump.

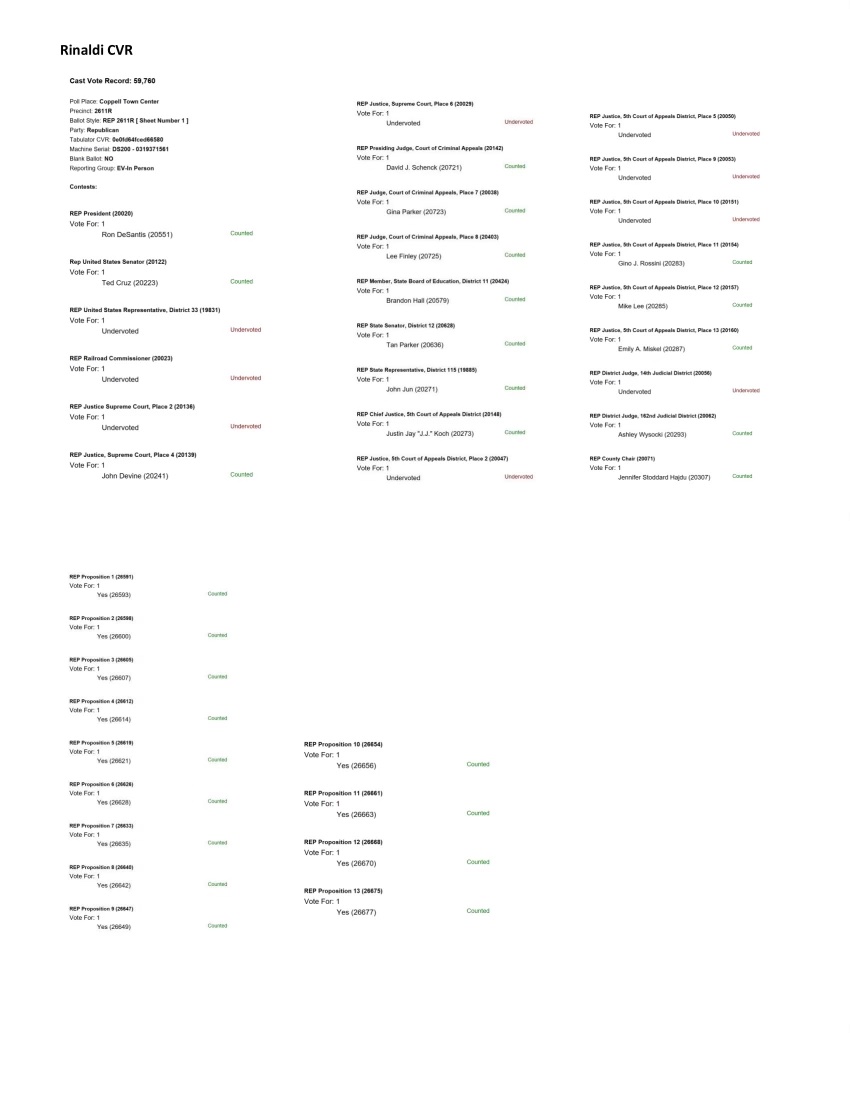

That’s not what the ballot and cast vote record images (below) show. Instead, Rinaldi allegedly voted for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R), whose campaign collapsed in an embarrassing sputter in Iowa months earlier.

Ballot allegedly cast by Texas GOP Chair Matt Rinaldi

Alleged Cast Vote Record (CVR) for Matt Rinaldi.

Reporters with Current Revolt “independently verified the precinct and reporting group information, all showing a match” between the above ballot and Rinaldi’s identification data. As their report noted, the vulnerability created by the unique ballot numbers exists in “about 90% of Texas counties,” including all the largest ones: Harris, Dallas, Tarrant, Bexar, and Travis, the location of the state capital Austin.

A Texas data scientist, who asked to remain anonymous in order to speak freely due to the threat of political reprisals that are already swirling around the Lone Star State, described the methodology to Mediaite for matching the unique identifier ballot numbers with voter names. It was a bit more complicated than just pasting text from a foreign language into Google Translate, he said, requiring only a “simple” formula in Microsoft Excel that is among the built-in functions and “anyone can learn how to do with a basic Google search.”

The data scientist added that he was personally able to replicate this unveiling of actual ballots tied to real voter names using information obtainable through public information requests, tying the specific numbers on the ballots to voter ID files, and matched with precinct location data and timestamps.

Ballot confidentiality could potentially have an even lower level of protection in small, rural counties, the data scientist explained, because knowledge of Excel formulas or decryption of the voter numbers is not needed where there are so few voters that it’s easy to match the timestamp of when a voter number was assigned at check-in to the timestamp on a ballot being cast minutes later.

Even more troubling, the data scientist mentioned multiple additional methods for using the public election data to match names to ballots, which I am refraining from describing here in detail, that were even easier and didn’t require any Excel expertise.

The Texas GOP’s general counsel put out a statement calling the story “absurd” and stating that she had instructed Rinaldi not to comment, but, as many commenters pointed out, there wasn’t an actual denial in her statement, just a vague threat that the party would “investigate potential civil and criminal acts including defamation.”

Current Revolt’s Tony Ortiz responded on The Platform Formerly Known as Twitter, writing there was a public lawsuit but “[t]he RPT has never commented or cared about this suit until today,” and urged the party to join the efforts to “work towards securing our elections” instead of “lashing out at those who have identified clear problems and vulnerabilities” in the system.

“Threatening to sue the journalist who exposed our election vulnerabilities instead of recognizing it’s an issue and committing to fixing it really says a lot about the current state of the Republican Party of Texas,” Ortiz added.

“The harms Plaintiffs have suffered are real, not theoretical, and will continue to occur at each future called election unless and until this Court orders Defendants to comply with the law,” the complaint states before asking for declaratory judgment that the defendant officials’ actions violated their rights under the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment and Free Speech clause of the First Amendment, an injunction ordering them to stop using the “computerized random unique identifier tracking and numbering of ballots that do not preserve the secrecy of Plaintiffs’ ballots” and the technology software and devices that “do not preserve the secrecy of Plaintiffs’ ballots,” and attorneys’ fees and costs.

With the current technology used by the counties being in place for several years, and by so many counties covering such a large segment of the Texas population, there are potentially millions of voters’ ballots that are vulnerable to exposure. Considering the divisive nature of our current political climate — that all too often devolves into harassment, intimidation, and even actual violence — this has created a real and terrifying risk for many Texans. The complaint tells how this fear led the plaintiffs to forego voting in recent local elections that took place after they learned about this vulnerability with the in-person ballots.

One big question looming out there is who exactly knew about this vulnerability before the lawsuit was filed, and if they have exploited it to intimidate or coerce anyone? Moreover, until this vulnerability is fixed and the state government requires the counties to use the legally-mandated and secure consecutive ballot numbering, the data files are a tempting risk for hackers and other cybersecurity problems — exacerbated by the collection of all this data in one central database at the state level.

These county and state election data files are public record under Texas law. The 89th Texas legislative session does not kick off until January 2025, an excessive amount of time to leave Texans’ voting records compromised. Texans who wish to keep their November ballots confidential may soon be urging Abbott to call a special session to address this problem.

Pressley v. Nelson lawsuit by Sarah Rumpf on Scribd

–